Benin

Things to Do

Natitingou

|

|||||

Everywhere you go in Benin you will hear people talking of Natitingou and it will be taken

as a fact that, as a tourist, you will be visiting the town. So it comes as something of a suprise to

discover that the town is not quite the exotic golden city that you are led to believe. In fact

it only just qualifies as a town nad not a very exiting one at that.

Think of Natitingou not as an attraction and a goal in itself, but instead as a quiet and pleasant place

in which to rest up and prepare for the great adventures that are hidden in the surrounding countryside.

In town itself the Petit Marché (small market) just south of the roundabout, is a colourful affair

with a good ambiance and opportunities for souvenir hunters. Keep an eye out for the bright red ball-like

lumps on sale everywhere. They're the local cheese and it's famous all over Benin.

But at the end of the day it's the tribes, mountains and wildlife of the surrounding region that are

the main reason for visiting Natitingou.

Musée d'Arts et de Traditions Populaires

|

|||||

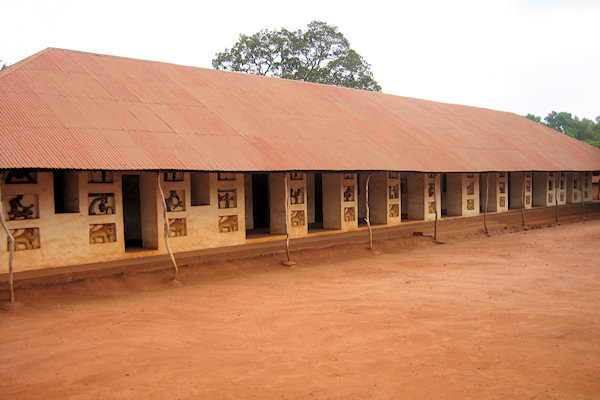

The Musée dÁrts et de Traditions Populaires, housed in a colonial building built by slaves

at the beginning of the 20th century, gives an overvieuw of life in Somba communities.

The exibition includes various musical instruments, jewellery, crowns and artefacts.

Most interesting is the habitat room, which has models of the different types of Tata Somba.

The Somba

|

|||||

Commonly referred to as the Somba, the Betamaribé people are concentrated to the southwest of

Natittingou in the plains of Boukoumbé on the Togo border.

They live in the middele of their cultivated fields, rather than together in villages, so their compounds

are scattered over the countryside. This custom is a reflection of their fierce individuality, which has

seen them resist both Dahomey slave hunters and the advance of Christianity ans Islam.

The Betamaribé's principle religion is animism - as seen in the rags and bottles they hang from trees.

Once famous for their nudity, they began wearing clothes in the 1970s.

What's most facinating about the Betamaribé is their Tata Samba houses - round, tiered huts that

look like miniature forts with clay turrets and thatched spires. The ground floor of a house is mostly

reserved for livestock and defence mechanisms. A stepladder leads from the kitchen to the roof terrace,

where there are sleeping quarters and grain stores.

The beautiful, fine scarification on their faces and their bellies are the marks of the strict initiation

rites into adulthood.

Tanéka villages

|

|||||

The villages themselves appear from a distance to be just like any other African village, but once

inside the middle of them you will realise that all of the buildings are actually far smaller than you

originally thought and it's hard to believe that anyone can actually fit inside the houses. It's as if

the entire village has shrunk in the wash.

Though their houses and villages might be very different from those of the more famous Smba to the north

the two groups retain a lot of cultural similarities as well as much of their traditional tribal

lifestyle.

It's not at all unusual to see men returning from a hunt with spears, whilst many others sit around the

village smoking long bone pipes.

The most important people in the community remain the headman and the guérisseur

Fulani

|

|||||

The Fulani live across a huge swath of central and western Africa, from Senegal in the west

and to Sudan in the east. They are bounded in the north by the Sahara Desert and live no further south

than Cameroon and the Central African Republic.

Historically, the Fulani are a nomadic people who traveled from one region to another, seeking water

for their cattle herds. After migrating from North Africa or the Middle East, they gradually spread

eastward (over a 1000 year period from A. D. 900 to 1900), from Senegal and Guinea to as far as Sudan.

While some Fulani maintain the tradition of nomadic wandering, and others remain in one location permanently,

the most favored and widespread way of living is semi-nomadic.

The hot, tropical climate of north-central and western Africa provides only two seasons - wet and dry. The

semi-nomadic Fulani revolve their lives around these seasons, and around a strict division of labor based

on gender.

During the wet season, the cattle, sheep, and goats remain at a permanent settlement where they are herded

by the men and boys, but usually milked and cared for by the women and girls. The men plant, care for and

harvest the crops; which mostly consist of millet, rice, and peanuts.

During the dry season, the Fulani practice the nomadic part of their existence. Rather than risking the

exhaustion of the village water supply, the young men leave the older men, the women, and the children

in the village and take the cattle on a search for alternative water supplies until the rainy season

approaches. These nomadic bands camp in portable shelters of poles or branches covered with straw, leaves,

or mats.

Savalou - Dankoli fetish

|

|||||

Ten kilometers out of town on the road to Djougou is the Dankoli fetish

To the uninitiated this roadside may just resemble a rotting, stinking pile of organic rubbish and blood,

but don't be fooled, for the Dankoli fetish is, in actual fact, the strongest and most powerful

fetish in the country. the gods are so close here that you don't even need a priest to act as a middleman

between you and the gods.You simply speak directly with the spirits who will pass on your message and

requests.

It's said that anything you ask for will become true within a year. This is a popular site of pelgrimage

with a stream of believers looking for answers arriving all the time.

It's perfectly possible for foreigners to make a request to the gods here as well; to do so you must firts

buy a wooden peg off the Vodounon (priest) and hammer it into the main fetish whilst making your

request (which you should keep secret) and promising to return to make a sacrifice when your request is

answered. Seal the deal by poring some palm oil on to your stake and repeating teh request and sacrificial

promise again. You must than spit a mouthful of the specially prepared rum at your stake whilst repeating

your request again.

Then move over to the Legba representation (a huge penis sticking out of the ground) and repeat

the oil-pouring, rum-spitting process again, before moving to the two holes in the ground called les

Jumeaux (the twins) and repeat the process again.

Of course, even gods need a littleincentive to grant wishes so you must finally return to our wooden peg

and place a suitablefinancial donation next to it which you then pour more oil and rum on to and

voilà, one year later you'll have whatever you wished for, but don't forget to return and make

your sacrifice because nothing irks the gods as much as not getting what was promished to them.

Bohicon

Bohicon is not a place to actually visit, but a placeto pass through - often quickly as possible,

en route to or from Abomey.

In actual fact this large and entirely modern town is not a bad place and the market is a sprawling giant

of an affair that is far away the biggest market in central Benin.

Even with this draw, however, most people consider the town (which was built by the French just after

their succesful occupation as a way to reduce the influence of Abomey) as nothing but a transport junction.

Abomey

|

|||||

The name is mythical, and not without reason: Abomey was the capital of the fierce

Nowedays Abomey is a rather quiet place, although the numerous ruins and artefacts left behind by the

kings of Dahomey make it clear it wasn't always so.

In fact, the French were so fearfull of Abomey's power that they deliberately designed the railway line

between Cotonou and Parakou so that it would run 9km east of Abomey in what is now Bohicon.

In the city centre is the Place de Goho with the Gbêhanzin statue Gbêhanzin (12th king;

ruled 1889-1894) agreed to sign a treaty here with Colonel Dodds and the French forces - goho

means "meeting'

Dahomey Kingdom

|

|||||

According to legend, the dynasties of the kingdoms in the south of the Republic of Benin originated

in Tado, a town in present-day Togo, and were born of a mythical couple - Princess Aligbonon

of Tado and a panther.

In the 17th century, two of their descendants, Ganyé Hessou and Dako, laid the foundations

of a new kingdom: Danhomè.

As Dahomey's kings embarked on wars to expand their territory, they began using rifles and other firearms

traded with French and Spanish slave traders for young men captured in battle, who fetched a very high

price from the European slave merchants.

Under King Agadja (ruled 1708-1732), the kingdom conquered Allada, where the ruling family originated.

They thus gained direct contact with European slave traders on the coast. Nevertheless, Agadja was unable

to defeat the neighbouring kingdom of Oyo, Dahomey's chief rival in the slave trade. By 1730, he became a

tributary of Oyo. This means that Dahomey had to pay a yearly duty of heavy taxes, but otherwise remained

mostly independent.

Even as a tributary state, Dahomey continued to expand and flourish because of the slave trade and later

through the export of palm oil from large plantations that emerged. Because of the economic structure of

the kingdom, the land belonged to the king, who had a virtual monopoly on all trade.

Dahomey - Abomey Historical Museum

|

|||||

The Abomey Historical Museum was created by the French colonial administration in 1943. With a surface

of about 5 acres, it is situated on the palatial site and comprises the palaces of King Guézo and

King Glèlè.

Like all the palaces, the Abomey Museum is made up of buildings and courtyards which are surrounded in

places by enclosures and walls of impressive height. The average thickness of the walls is about one and

a half feet which ensures an agreeable temperature inside the rooms.

Some buildings incorporate bas-reliefs, originally simple decorations which became a real codified

means of communication at the end of the 18th century. The bas-reliefs inlaid in walls and pillars were

modelled out of earth from ant-hills mixed with palm oil and dyed with vegetable and mineral pigments.

They represent one of the most impressive highlights of the Museum.

Each palace is made up of more or less similar units from the point of view of form and function. Access

to the first interior courtyard (Kpododji) of the palace is by the Honnouwa, and the second

interior courtyard (Jalalahènnou) by the Logodo. The second courtyard contains the

Ajalala (a superb building with a variety of openings and where the walls are decorated with

evocative designs in bas-relief); the Zinkpoho (exhibition room for the royal thrones) and

temples.

The tomb of King Glèlè, still has a bed in it and plates of food laid out so that his spirit does

not become hungry. It remains a tradition to this day that on market day one of the current crop of

princesses comes to the tomb to clean it, change the bed sheets and put out fresh food and drink for the

king's spirit. Before leaving she sings a song to encourage the spirit to come foreward and than leaves the

tomb. After a few minutes, during which time the king's spirit will have taken the food and drink he

requires, she returns to the chamber and sings another song to send the spirit peacefully on his way back

to the other world.

The Abomey Historical Museum contains 1,050 objects representing principally the property of the kings

who reigned over Danhomè.

The collections are made up of arms, thrones carved in one block of wood (each king had one or several

thrones which he used during important ceremonies), jewellery, portable altars in metal ("assin")

dedicated to ancestors or deceased kings whose spirits they represent, and sculptured animals symbolising

the kings.

Kétou - Yoruba people

|

|||||

Kétou was the former centre of a small but powerful Yoruba Kingdom.

Contemporary historians as well as Yoruba legend contend that the Yorubas are not indigenous to

Yorubaland, but are descendants of immigrants to the region.

It is believed that the forefather of all the Yoruba people was an important man called Oduduwa -

a Prince from the royal family in Mecca. At that time, the people of Mecca including the royal family

were worshipers of different idols and deities. When the Islam religion was adopted by the royal family

and introduced to the kingdom of Mecca, Oduduwa rebelled refusing to convert to Islam. This caused a split

in the royal family. As a result, Oduduwa was expelled and forced into exile. According to legend, he

gathered all the men and women loyal to him numbering thousands and began a journey.

He headed southwest from mecca and established his kingdom in a place what is now Yorubaland in

modern day Nigeria and Benin.

One of the features that make the Yoruba unique is their tendency to form into large city groups instead

of small village groups. Most of the large cities of Nigeria and Benin are inhabited almost solely by

Yoruba.

It's possible to visit the "King of Kétou"; quite a nice experience.

Gelede Dance

|

|||||

Gelede is an annual festival honouring “our mothers” (awon iya wa), not so much for

their motherhood, but as female elders.

It takes place in the dry season (March-May) among the Yoruba people of south-west Nigeria and

neighbouring southeast Benin.

The mask (or headdress, since it does not cover the face) is one of a pair worn together by men

masquerading as women to amuse, please and placate the mothers who are considered very powerful, and

may use their powers for good or destructive witchcraft purposes.

The Gelede ceremony involves carefully choreographed dance, singing and music, especially drumming.

Dozens of masquerading pairs may take part.

Gelede probably originated in the late 18th or early 19th century. It may be associated with the change

from a matriarchal to a patriarchal society, but then one might expect it to have older beginnings.

The Gelede ceremony may also take place at the funerals of cult members or in times of drought or other

serious situations which are thought to have been brought about by malevolent witchcraft.

It's possible to witness a Gelede dance at the city of Cové