China

Things to DO

Khunjerab Pass

|

|||||

The highway over Khunjerab Pass (4.733m) was opened to foreigners in may 1986 and closed again in april 1990. The official

excuse was landslides, but the real reason was a political "eartquake". However in august of the same year it opened again but

only for individual travel from Pakistan to Kashgar.

Khunjerab means "Valley of Blood", a referens to local bandits who took advantage of the terrain to plunder caravans and slaughter

the merchants.

The rough section between the Pakistan border and Kashgar still needs a few more years before it can be called a road. Facilities en

route are being steadily improved, but take warm clothing, food and drink on board with you - once stowed on the roof of the bus your

baggage is not easily accesible.

However you travel through stunning scenery; high mountain pastures with grazing camels and yaks tended by Tajiks who live in yurts.

Kashgar

In the early part of this century,

Traders from India tramped to Kahgar via Gilgit and the Hunza Valley; in 1890 the British sent a trade agent to Kashgar to represent

their interests and in 1908 they established a consulate.

As with Tibet in the 1890's, the rumours soon spread that the Russians were on the verge of gobbling up Xinjiang. Contact with the Soviet

Union seemed to make sense given the geographical location of Kashgar.

Ethnically, culturally, linguistically and theologically the inhabitants of

|

|||||

Kashgar had absolutely nothing in common with the Chinese and everything in common with the Muslim inhabitants on the other side of

the border.

Whereas it took a five-month camel and donkey ride to get to Beijing and a five or six-week hike to reach the nearest railhead in British

India, the soviet railhead in Osh was more accessible and from Kashgar strings of camels would stalk westward with their bales of wool,

returning with cargoes of Russian cigarettes, matches and sugar.

When the Communists came to power the city walls were ripped down and a huge, glinstering white statue of Chaiman Mao was erected

on the main street. The statue stands today hand outstreched to the sky above and the lands beyond, a constant reminder to the local populace

of the alien regime that controls the city.

Above 200.000 people live here, and apart from the Uyghur majority this number includes Tajiks, Kirghiz and Uzbekh. The number of Han

Chinese living here is relatively small, although PLA troops are always conspicuous and there are plenty of Han plainclothes police.

|

|||||

The big yellow-tiled Id Kah Mosque is one of the largest in China, with a courtyard and gardens that can hold 20.000 people.

It was built in 1442 as a smaller mosque on what was the outskirts of town. During the Cultural Revolution, China's decade of

political anarchy from 1966 to 1976, Id Kah suffered heavy damage, but has since been restored.

Sprawiling all around Id Kah are roads full of Uyghur shops and narrow passages lined with adobe houses the seems trapped in a time warp.

Blacksmiths pound away on anvils, colourfully painted wooden saddles can be bought and you can pick your dinner from a choice line-up of

goats' heads and hoofs.

Old Asian men with long thick beards, fur overcoats and high leather boots swelter in the sun. The Muslim Uyghur woman here dress in

skirts and stockings have a much greater prevalence of faces hidden behind veils of brown gauze than in other cities.

|

|||||

Once a week Kashgar's population swells by 50.000 as people stream in to the Sunday Market - surely the most mind-boggling

bazar in Asia and not to be missed.

By sunrise the roads east of town are a sea of pedestrians, horses, bikes, motorcycles, donkey carts, trucks and belching tuk-tuks,

everyone shouting "boish-boish!" (coming through!).

In arenas off the livestock market, men test-ride horses or look into sheep's mouths.

A wonderful assortment of people sit by their rugs

and blankets, clothing and boots, hardware and junk, tapes and boomboxes - and, ofcourse, hats. In fact the whole town turns into a

bazar, with hawkers everywhere.

Beware of pickpockets.

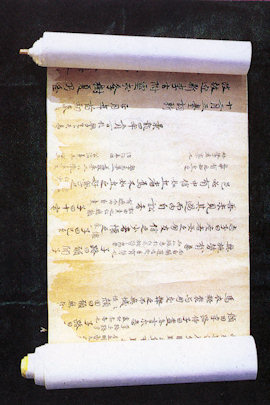

Kuqa

According to the Book of Han (completed in 111 AD), Kucha was the largest of the Thirty-six Kingdoms of the Western

Regions, with a population of 81.317, including 21.076 persons able to bear arms.

Buddhism was introduced to Kuqa before the end of the 1st century AD, however it was not until the 4th century that the kingdom

became a major center of Buddism, primarily Sarvastivada, but eventually also Mahayana Buddism during the Uyghur period.

|

|||||

According to the Book of Jin, during the third century there were nearly thousand Buddhist stupas and temples in Kuqa.

At this time Kuqanese monks began to travel to China.

The fourth century saw yet further growth of Buddism within the kingdom. The palace was said to resemble a Buddhist monastry, displaying

carved stone buddhas and monasteries around the city were numerous.

Saddly, modern Kuqa retains little, if any of its former glory.

Kuqa Mosque is the second largest mosque in Xinjiang. The mosque was constructed in the 16th cententury AD, when the founder of

Ishan movement – Iskhak Valy came to Kuqa from Kashgar and spread his teaching in Kuqa.

The large prayer hall, which can hold 1.000 prayers, is supported by 88 pillars with carved motifs.

Over the past few hundred years, this building has endured fires, earthquakes and erosion, it was rebuilt in 1931.

|

|||||

The Kizil Caves, located on the northern bank of the Muzat River 65 kilometres west of Kuqa, is the largest of the ancient

Buddhist cave sites that are associated with the ancient Tocharian kingdom of Kuqa.

There are 236 cave temples in Kizil, carved into the cliff stretching from east to west for a length of 2 km. Of these, 135 are still

relatively intact.

The earliest caves are dated, to around the year 300 AD.

Most researchers believe that the caves were probably abandoned sometime around the beginning of the 8th century, after Tang influence

reached the area.

Although the site has been both damaged and looted, around 5.000 square metres of wall paintings remained. These murals mostly depict

Jataka stories, Avadanas, and Legends of the Buddha, and are an artistic representation in the tradition of the

Hinayana school of the Sarvastivadas.

According to a text found in Kucha, the paintings in some of the caves were commissioned by a Tokharian king called "Mendre" with

the advice of Anandavarman, a high-ranking monk.

Turpan

A green oasis in the middle of the desert, blown by winds from all directions – this was the way how Turpan city appeared before the eyes of weary travelers over a period of two thousand years.

|

|||||

It was not only an important commercial and cultural center on the Great Silk Road, but also a strategic post on the ancient

caravan route northern branch.

Turpan is a unique city. It is located in the Turpan Basin at the depth of 154 m below sea level. From all sides the city is surrounded

by deserts and mountains, destroyed medieval towns and ruins of ancient settlements.

The locals named Turpan as "Fire Land”, because it is the hottest city in China and one of the driest places in the world. In summer

the temperature reaches 50°C in the shade.

The city owes its prosperity to the ancient kyariz irrigation system that the Uyghurs adopted from the ancient Persians.

Every year, the melt water from the slopes of the Tien Shan Mountains, flowing down the Turpan valley, is stored by means of a system of

underground irrigation canals with a total length of about 5 kilometers, preventing it from evaporation at high temperatures.

|

|||||

From ancient times, Grape Valley has been famous for the cultivation of the sweetest, tastiest grapes. There is a winery near the

valley and lots of well-ventilated brick buildings for drying grapes - wine and raisins are major exports od Turpan.

The Flaming Mountains received their name from a fantasy account of a Buddhist monk, accompanied by a Monkey King with magical

powers. The monk runs into a wall of flames on his pilgrimage to India in the popular 16th century novel, Journey to the West, by

Ming dynasty writer, Wu Cheng'en.

The novel is an embellished description of the monk Xuanzang who traveled to India in 627 AD to obtain Buddhist scriptures

The Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves, were carved over a 900 year-long period of time between about 400 and 1,300 AD.

Much of the artwork was destroyed intentionally by Muslims destroying the idolatry in the caves or by European archeologists and others

cutting out the artwork for museums around the world or maybe for sale.

When trade opened up between the Han Empire and western countries about 100 BC, Gaochang was a major stop because there

|

|||||

was water and food to supply the travelers. The Han Dynasty used it as a garrison about 50 BC.

But empires and kingdoms contested the site, because the people who controlled the city had control of trade.

The Uyghurs came to the area in the middle of the 9th century. They submitted to Genghis Khan of the expanding Mongol Empire

at the beginning of the 13th century.

When the Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) fell, there was a disruption of trade through the area. Warfare between the Uighurs and

Mongolians damaged the city, and it was burnt down in the 14th century.

A large community of Chinese lived in Gaochang and buried their people in the Astana Tombs from the late 200s to the late 700s.

About 500 tombs are excavated; a lot of the original material is in museums in other countries.

There was often a funerary banner depicting the Chinese myth about Fuxi and Nuwa who created

the world.

|

|||||

Turpan Museum is regarded as the second largest museum in Xinjiang and was first completed in 1989.

This exhibition hall is mainly to show selected cultural relics that have been unearthed, levied, picked and donated since the founding

of the People’s Republic.

There were human traces in this area as early as the Stone Age. It entered the Bronze Age about three thousand years ago.

The Han Dynasty (206BC - 220AD) first annexed it to China’s territory in 60BC.

About 400 years later, the Gaochang Prefecture and the Gaochang Kingdom were established here successively.

It returned to the central government of China when the Tang Dynasty (618-907) united the nation.

Turpan’s history is created by people of different tribes and ethnic groups (including some from Central Asia), cultures and religions.

The 900-square-meter exhibition hall means to represent panoramic picture of the region and these periods.

There are more than 20,000 pieces of cultural relics in the Turpan Museum and among these 707 pieces are precious ones.

The collections of the Museum include stoneware, pottery, clay figurines, carpentry, bronze ware, ironware, gold and silver works,

documents, woodcarvings, paintings, dried corpses, grains, dried fruits and textiles, etc.