Guatemala

Historie

The first evidence of human habitation in Guatemala dates back to 12.000 BC. There is archaeological proof that early Guatemalan

settlers were hunters and gatherers.

Archaeologists divide the pre-Columbian history (meaning the time before the arrival of Christopher Columbus) of

Mesoamerica into the Preclassic period (2.999 BC to 250 AD), the Classic period (250 to 900 AD), and the

Postclassic period (900 to 1500 AD)

Until recently, the Preclassic was regarded as a formative period, with small villages of farmers who lived in huts, and few

permanent buildings. However, this notion has been challenged by recent discoveries of monumental architecture from that period.

The Classic period of Mesoamerican civilization corresponds to the height of the Maya civilization, and is represented by

countless sites throughout Guatemala, although the largest concentration is in Petén. This period is characterized by

heavy city-building, the development of independent city-states, and contact with other Mesoamerican cultures. This lasted until

the Maya abandoned many of the cities of the central lowlands or were killed off by a drought-induced famine.

The Post-Classic period is represented by regional kingdoms, such as the Itza, Ko'woj, Yalain and Kejache

in Petén, and the Mam, Ki'che', Kackchiquel, Chajoma, Tz'utujil, Poqomchi', Q'eqchi'

and Ch'orti' in the Highlands. Their cities preserved many aspects of Mayan culture, but never equaled the size or power of

the Classic cities.

After arriving in what was named the New World, the Spanish started several expeditions to Guatemala, beginning in 1519. Before

long, Spanish contact resulted in an epidemic that devastated native populations. Hernán Cortés, who had led the Spanish conquest

of Mexico, granted a permit to Captain Pedro de Alvarado, to conquer this land. Alvarado at first allied himself with the

Kackchiquel nation to fight against their traditional rivals the Ki'che' nation. Alvarado later turned against the

Kaqchikel, and eventually held the entire region under Spanish domination.

From 1524 until 1821, Guatemala was the center of government for the Captaincy-general of Guatemala, whose jurisdiction

extended from Yucatán to Panama. Economically, this was mainly an agricultural and pastoral area in which Amerindian labor served a

colonial landed aristocracy. The Roman Catholic religion and education regulated the social life of the capital. Spanish political and

social institutions were added to Amerindian village life and customs, producing a hybrid culture.

In 1821, the captaincy-general officially proclaimed its independence from Spain. After a brief inclusion within the Mexican Empire of

Agustín de Iturbide (1822–23), Guatemala, along with present-day Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua, formed the

United Provinces of Central America in 1824. This federation endured until 1838–39. Guatemala proclaimed its independence

in 1839 under the military rule of Rafael Carrera, an illiterate dictator with imperial designs. None of his ambitions were

realized, and he died in 1865.

Guatemala then fell under a number of military governments, which included three notable administrations: Justo Rufino Barrios

(1871–85), the "Reformer," who was responsible for Guatemala's transition from the colonial to the modern era; Manuel Estrada

Cabrera (1898–1920), whose early encouragement of reform developed later into a lust for power; and Jorge Ubico

(1931–44), who continued and elaborated on the programs begun by Barrios.

Despite their popularity within the country, the reforms of the Guatemalan Revolution were disliked by the United States government,

which was predisposed by the Cold War to see it as communist and the United Fruit Company (UFC), whose hugely

profitable business had been affected.

On 18 June 1954, a force armed by the CIA invaded Guatemala and backed by a heavy campaign of psychological warfare, including

bombings of Guatemala City.Thr invasion force fared poorly militarily, but the psychological warfare and the possibility of a U.S.

invasion intimidated the Guatemalan army, which refused to fight.

From 1960 to 1996, Guatemala endured a bloody Civil War fought between the U.S.-backed government and leftist rebels, which

included massacres of the Mayan population. The Guatemalan Civil War ended in 1996 with a peace accord between the guerrillas

and the government, negotiated by the United Nations through intense brokerage by nations such as Norway and Spain. Both sides made

major concessions. In 1999, U.S. president Bill Clinton stated that the United States was wrong to have provided support to

Guatemalan military forces that took part in the brutal civilian killings.

Since the end of the war, Guatemala has witnessed both economic growth and successful democratic elections, though it continues to

struggle with high rates of poverty, crime, drug trade, and instability.

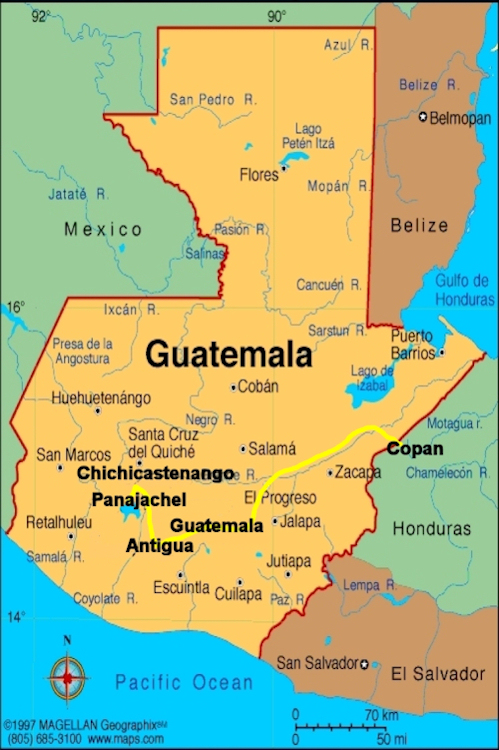

I have visited Guatemala in december 2004

It was part of my 30 days trip to Central America.

These are the places i have seen

Guatemala

Antigua

Chichicastenango

Panajachel

Please let me know when you're having questions.

i would be pleased to help you.

Things to do and other tips