Ireland

Historie

The earliest confirmed inhabitants of Ireland were Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, who arrived sometime around 7900 BC. The people

remained hunter-gatherers until about 4000 BC. It is argued this is when the first signs of agriculture started to show, leading to

the establishment of a Neolithic culture, characterised by the appearance of pottery, polished stone tools, rectangular wooden houses,

megalithic tombs, and domesticated sheep and cattle.

Some of these tombs, as at Knowth and Dowth, are huge stone monuments and many of them, such as the Passage Tombs of

Newgrange, are astronomically aligned. Four main types of Irish Megalithic Tombs have been identified: dolmens, court cairns,

passage tombs and wedge-shaped gallery graves.

The Céide Fields is an archaeological site on the north County Mayo coast in the west of Ireland, about 7 kilometres northwest of

Ballycastle, and the site is the most extensive Neolithic site in Ireland and contains the oldest known field systems in the world.

The systems consisted of small divisions separated by dry-stone walls. The fields were farmed for several centuries between 3500 BC and 3000 BC.

Wheat and barley were the principal crops.

The Copper Age begins around 2500 BC with the arrival of the Bell Beaker culture. The Irish Bronze Age begins around 2000 BC

and ends with the arrival of the Iron Age of the Celtic Hallstatt culture, beginning about 600 BC. The subsequent La Tène culture

brought new styles and practices by 300 BC.

The Romans referred to Ireland as Hibernia around AD 100. Ireland was never a part of the Roman Empire, but Roman influence was

often projected well beyond its borders.

Tradition maintains that in A.D. 432, St. Patrick arrived on the island and, in the years that followed, worked to convert the Irish

to Christianity. Patrick is traditionally credited with preserving and codifying Irish laws and changing only those that conflicted

with Christian practices. He is credited with introducing the Roman alphabet, which enabled Irish monks to preserve parts of the

extensive oral literature.

Ireland continued as a patchwork of rival kingdoms; however, beginning in the 7th century, a concept of national kingship gradually became

articulated through the concept of a High King of Ireland. Medieval Irish literature portrays an almost unbroken sequence of high kings

stretching back thousands of years, but modern historians believe the scheme was constructed in the 8th century to justify the status of powerful

political groupings by projecting the origins of their rule into the remote past.

The first recorded Viking raid in Irish history occurred in 795 AD when Vikings from Norway looted the island. The Vikings were expert

sailors, who travelled in longships, and by the early 840s, had begun to establish settlements along the Irish coasts and to spend the winter

months there. The Vikings never achieved total domination of Ireland, often fighting for and against various Irish kings. The great High King

of Ireland, Brian Boru, defeated the Vikings at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014 which began the decline of Viking power in Ireland

but the towns which Vikings had founded continued to flourish, and trade became an important part of the Irish economy.

One of the most prosperous reigns of any High King was the reign of Toirdelbach Ua Conchobhair (1106–1156). Under his rule, the first

castles in Ireland were built bringing improved defence and brought a new aspect to Irish warfare. He also built a naval base and castle at

Dún Gaillimhe.

By the 12th century, Ireland was divided politically into shifting petty kingdoms and over-kingdoms. Power was exercised by the heads of a few

regional dynasties vying against each other for supremacy over the whole island. One of these men, King Diarmait Mac Murchada of Leinster

was forcibly exiled by the new High King, Ruaidri mac Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair of the Western kingdom of Connacht.

Fleeing to Aquitaine, Diarmait obtained permission from Henry II to recruit Norman knights to regain his kingdom. The first Norman knights

landed in Ireland in 1167, followed by the main forces of Normans, Welsh and Flemings. Several counties were restored to the control of

Diarmait, who named his son-in-law, the Norman Richard de Clare, known as "Strongbow", heir to his kingdom.

This troubled King Henry, who feared the establishment of a rival Norman state in Ireland. Accordingly, he resolved to establish his authority.

In 1177, Prince John Lackland was made Lord of Ireland by his father Henry II of England at the Council of Oxford.

When John unexpectedly succeeded his brother as King John of England, the "Lordship of Ireland" fell directly under the English

Crown.

By the end of the 15th century, central English authority in Ireland had all but disappeared, and a renewed Irish culture and language, albeit

with Norman influences, was dominant again. English Crown control remained relatively unshaken in an amorphous foothold around Dublin known as

The Pale.

The title of King of Ireland was re-created in 1542 by Henry VIII, the then King of England, of the Tudor dynasty. English rule

was reinforced and expanded in Ireland during the latter part of the 16th century, leading to the Tudor conquest of Ireland. A

near-complete conquest was achieved by the turn of the 17th century, following the Nine Years' War (1593-1603).

From the mid-16th to the early 17th century, crown governments had carried out a policy of land confiscation and colonisation known as

Plantations. Scottish and English Protestant colonists were sent to the provinces of Munster, Ulster and the counties of

Laois and Offaly. These Protestant settlers replaced the Irish Catholic landowners who were removed from their lands. These

settlers formed the ruling class of future British appointed administrations in Ireland.

During the 17th century, Ireland was convulsed by eleven years of warfare, beginning with the Rebellion of 1641, when Irish Catholics

rebelled against the domination of English and Protestant settlers. The Catholic gentry briefly ruled the country as Confederate Ireland

(1642–1649) against the background of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms until Oliver Cromwell reconquered Ireland in 1649–1653 on

behalf of the English Commonwealth.

Ireland became the main battleground after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when the Catholic James II left London and the

English Parliament replaced him with William of Orange. The wealthier Irish Catholics backed James to try to to reverse the

Penal Laws and land confiscations, whereas Protestants supported William and Mary in this "Glorious Revolution" to preserve their

property in the country. James and William fought for the Kingdom of Ireland in the Williamite War, most famously at the Battle

of the Boyne in 1690, where James's outnumbered forces were defeated.

Under the emerging Penal Laws, Irish Roman Catholics and Dissenters were increasingly deprived of various civil rights, even the

ownership of hereditary property. Additional regressive punitive legislation followed in 1703, 1709 and 1728. This completed a comprehensive

systemic effort to materially disadvantage Roman Catholics and Protestant Dissenters while enriching a new ruling class of Anglican

conformists.

In 1800, following the Irish Rebellion of 1798, the Irish and the British parliaments enacted the Acts of Union. The merger

created a new political entity called United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland with effect from 1 January 1801. Part of the

agreement forming the basis of union was that the Test Act would be repealed to remove any remaining discrimination against Roman

Catholics, Presbyterians, Baptists and other dissenter religions in the newly United Kingdom.

The Great Famine of 1845–1851 devastated Ireland, as in those years Ireland's population fell by one-third. More than one million

people died from starvation and disease, with an additional million people emigrating during the famine, mostly to the United States

and Canada. In the century that followed, an economic depression caused by the famine resulted in a further million people emigrating.

A central issue throughout the 19th and early 20th century was land ownership. A small group of about 10.000 English families owned

practically all the farmland; Most were permanent residents of England, and seldom presented the land. They rented it out to Irish tenant

farmers. The late 19th century witnessed major land reform, spearheaded by the Land League under Michael Davitt that enabled

most tenant farmers to purchase their lands, and lowered the rents of the others.

The Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903 set the conditions for the break-up of large estates and gradually devolved to rural landholders,

and tenants' ownership of the lands.

In the 1870s the issue of Irish self-government became a major focus of debate under Charles Stewart Parnell, founder of the

Irish Parliamentary Party. Prime Minister Gladstone made two unsuccessful attempts to pass "Home Rule" in 1886 and 1893.

In September 1914, just as the First World War broke out, the UK Parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act 1914 to establish

self-government for Ireland, but it was suspended for the duration of the war. Before the war ended, Britain made two concerted efforts to

implement Home Rule, one in May 1916 and again with the Irish Convention during 1917–1918, but the Irish sides (Nationalist, Unionist)

were unable to agree to terms for the temporary or permanent exclusion of Ulster from its provisions.

In the December 1918 elections Sinn Féin, won three-quarters of all seats in Ireland, twenty-seven MPs of which assembled in Dublin

on 21 January 1919 to form a 32-county Irish Republic Parliament, the first Dáil Éireann unilaterally declaring sovereignty over the

entire island.

Unwilling to negotiate any understanding with Britain short of complete independence, the Irish Republican Army, the army of the newly

declared Irish Republic, waged a guerilla war (the Irish War of Independence) from 1919 to 1921. In the course of the fighting and

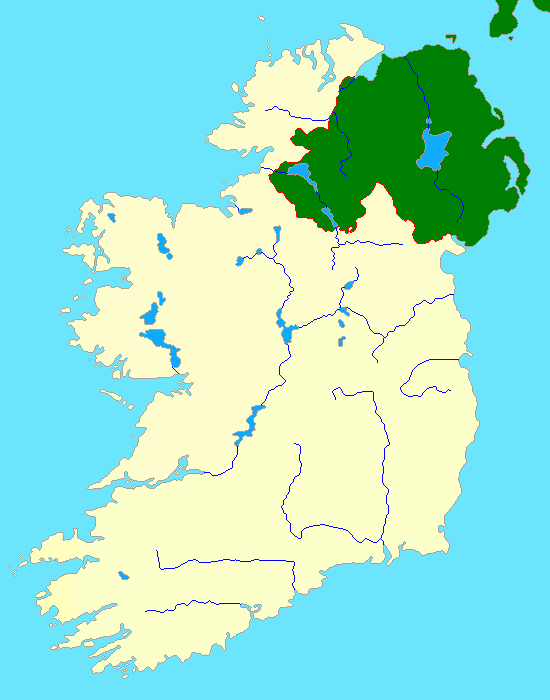

amid much acrimony, the Fourth Government of Ireland Act 1920 implemented Home Rule while separating the island into what the British

government's Act termed "Northern Ireland" and "Southern Ireland". In July 1921 the Irish and British governments

agreed to a truce that halted the war.

In December 1921 representatives of both governments signed an Anglo-Irish Treaty. This abolished the Irish Republic and created the

Irish Free State, a self-governing Dominion of the Commonwealth of Nations in the manner of Canada and Australia. Under the Treaty,

Northern Ireland could opt out of the Free State and stay within the United Kingdom: it promptly did so. In 1922 both parliaments ratified

the Treaty, formalising independence for the 26-county Irish Free State (which renamed itself Ireland in 1937, and declared itself

a republic in 1949); while the 6-county Northern Ireland, gaining Home Rule for itself, remained part of the United Kingdom.

In 1973, the Republic of Ireland joined the European Economic Community while the United Kingdom, and Northern Ireland as part of it,

did the same.

By the beginning of the 1990s, Ireland had transformed itself into a modern industrial economy and generated substantial national income

that benefited the entire nation. Although dependence on agriculture still remained high, Ireland's industrial economy produced sophisticated

goods that rivalled international competition.

I I have visited Ireland several times

The pictures of these trips, are not yet available; i have to digatalize them first.

Please let me know when you're having questions.

i would be pleased to help you.

Things to do and other tips