Romania

Historie

The Thracians were a group of Indo-European tribes inhabiting a large area in Central and Southeastern

Europe. They were bordered by the Scythians to the north, the Celts and the Illyrians to the west,

the Ancient Greeks to the south and the Black Sea to the east. It is generally proposed that a

proto-Thracian people developed from a mixture of indigenous peoples and Indo-Europeans from the time of the Early

Bronze Age.

By the 5th century BC, the Thracian presence was pervasive enough that Herodotus called them the second-most

numerous people in the part of the world known by him (after the Indians), and potentially the most powerful, if not

for their lack of unity. The Thracians in classical times were broken up into a large number of groups and tribes,

though a number of powerful Thracian states were organized, such as the Odrysian kingdom of Thrace and the

Dacian kingdom of Burebista.

The Southern part of Thrace was conquered by Philip II of Macedon in the 4th century BC and was ruled by the

kingdom of Macedon for a century and a half. During the Macedonian Wars, conflict between Rome and Thracia was inevitable.

The destruction of the ruling parties in Macedonia destabilized their authority over Thrace, and its tribal authorities

began to act once more on their own accord. After the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC, Roman authority over Macedonia

seemed inevitable, and the governing of Thracia passed to Rome. Neither the Thracians nor the Macedonians had yet

resolved themselves to Roman dominion, and several revolts took place during this period of transition.

During the 3rd century AD, with the invasions of migratory populations (Goths, Huns, Slavs) the Roman Empire was forced

to pull out of Thrace.

In the Middle Ages, Romanians lived in three distinct principalities: Wallachia, Moldavia and

Transylvania.

By the 11th century, Transylvania had become a largely autonomous part of the Kingdom of Hungary.

In Wallachia and Moldavia, many small local states with varying degrees of independence developed. Only in the 14th

century did the larger principalities of Wallachia (1310) and Moldavia (around 1352) emerge to fight the threat of

the Ottoman Empire.

By 1541, the entire Balkan peninsula and most of Hungary had become Ottoman provinces.

In 1699, Transylvania became a territory of the Habsburgs' Austrian empire following the Austrian victory over

the Turks in the Great Turkish War. The Habsburgs in turn expanded their empire in 1718 to include an important

part of Wallachia and in 1775 to include the northwestern part of Moldavia. The eastern half of the Moldavian

principality was occupied in 1812 by Russia.

After the failed 1848 Revolution, the Great Powers did not support the Romanians' expressed desire to

officially unite in a one single state, which forced them to proceed alone with their struggle against the Ottomans.

The electors in both Moldavia and Wallachia chose in 1859 the same leader Alexandru Ioan Cuza to be their

Ruling Prince. Thus, Romania was created as a personal union, albeit without including Transylvania. There, the upper

class and the aristocracy chose to remain under Hungarian rule, even though the Romanians were by far the most numerous

ethnic Transylvanian group and constituted the absolute majority.

In August 1915, about a year after the start of World War I, Romania tried to maintain neutrality. One year

later, under significant pressure from the Allies, on 27 August 1916 Romania joined the Allies, declaring war on

Austria-Hungary. For this action, under the terms of the secret military convention, Romania was promised

support for its goal of national unity of all the territories populated with Romanians.

By the war's end, both Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires had collapsed and disintegrated; Transylvania proclaimed

their unification with the Kingdom of Romania in 1918.

As World War II ended, Romania, a former Axis member, was occupied by the Soviet Union, the sole representative of

the Allied powers. On 6 March 1945, a new pro-Soviet government that included members of the previously outlawed

Romanian Communist Party was installed.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Nicolae Ceausescu became head of the Communist Party (1965), head of state (1967) and

assumed the newly established role of President in 1974. Ceausescu's denunciation of the 1968 Soviet invasion of

Czechoslovakia and a brief relaxation in internal repression helped give him a positive image both at home and in the

West. However, rapid economic growth fueled by foreign credits gradually gave way to an austerity and political

repression that led to the fall of his totalitarian government in December 1989.

After the revolution, the

The subsequent disintegration of the Front produced several political parties including the Social Democratic

Party, the Democratic Party and the Alliance for Romania. The former governed Romania from 1990

until 1996 through several coalitions and governments with Ion Iliescu as head of state. Since then there have been

several democratic changes of government: in 1996 the Democrat-Liberals' opposition and its leader Emil

Constantinescu acceded to power; in 2000 the Social-Democrats returned to power, with Iliescu once again as

president; and, finally, in 2004 Traian Basescu was elected president, with an electoral coalition called

Justice and Truth Alliance. Basescu was narrowly re-elected in 2009.

I will visit Romania in may 2014.

On that trip i have seen

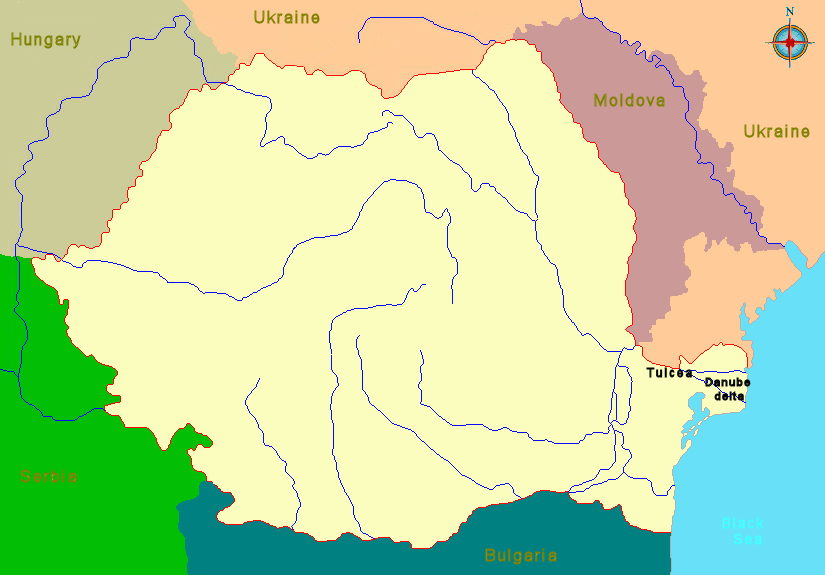

Tulcea

Danube Delta

Please let me know when you're having questions.

i would be pleased to help you.

Things to do and other tips